Five reasons Adam Smith remains Britain’s most important economist, 300 years on

June 5 2023 marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Adam Smith, the 18th-century British economist widely hailed as the father of modern economics.

Born in Kirkcaldy, on the east coast of Scotland, Smith studied at the University of Glasgow and at Balliol College, Oxford (which he didn’t think highly of), before becoming a professor of moral philosophy at Glasgow. He was a quiet, unassuming man, only travelling when he accompanied a student on a tour of Europe in the 1760s. He died in Edinburgh in 1790.

Despite living an uneventful life, Smith is considered a central figure in the Scottish Enlightenment. His book Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, remains one of the most influential books ever written – second only to Karl Marx’s Das Kapital as the most cited work of classical economics of all time.

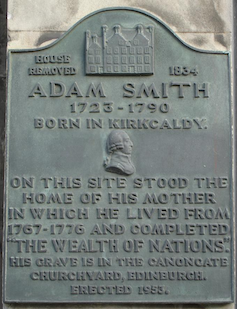

A plaque on Kirkcaldy High Street.

James Eaton-Lee, CC BY-SA

As my research shows, Smith is much more than the “father of economics”. He was a philosopher, a historian, and a political theorist. His life work was dedicated to working out the moral, social and political consequences – both good and bad – of the emerging capitalist and industrial economy in late 18th-century Britain. Here are five reasons why he remains Britain’s most important economist.

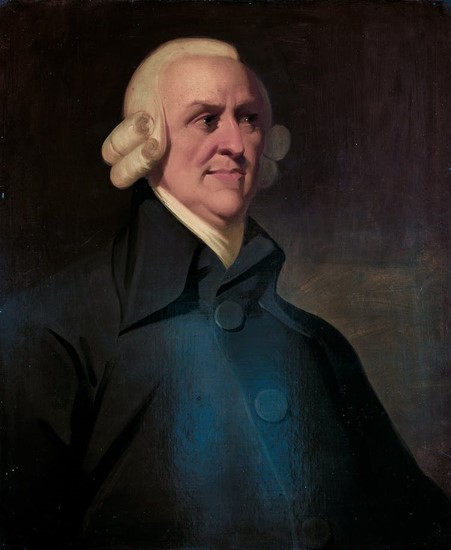

The Muir Portrait of Adam Smith, c 1800, artist unknown

Scottish National Gallery

1. He invented fundamental economic concepts

Among the concepts Smith came up with – or helped to popularise – are productivity, free markets and the division of labour. His use of “the invisible hand” to describe the unseen mechanisms that regulate the market economy remains a central metaphor in contemporary economic thinking.

In the 19th century, economists inspired by Smith, including David Ricardo, laid the foundations of economics as the discipline we know today, by formalising economic reasoning in mathematical language. Smith’s innovative discussion of the rules of supply and demand anticipated the economic model of general equilibrium. His theory of economic growth also inspired later economists such as John Maynard Keynes to develop the notion of gross domestic product.

2. He has a cult following

Smith was already famous in his lifetime, even before he published Wealth of Nations. As a professor of moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow between 1753 and 1763, his reputation attracted students from as far away as Russia.

However, in the 20th century, he became something of a hero for proponents of free markets. An influential thinktank founded in the 1970s, the Adam Smith Institute – dedicated to the pursuit of economic liberalism – bears his name. And as prime minister, Margaret Thatcher supposedly carried a copy of Wealth of Nations in her handbag.

Smith is widely celebrated –- often by people who haven’t read all his works –- as a prophet of individualism and neoliberalism. People see him as the man who foresaw the rise of industrial capitalism and provided definitive arguments against the idea of government interference. This, however, is a caricature of his writings.

Wealth of Nations was not a celebration of individualism. Smith was all too aware of the dangers and drawbacks of unbridled capitalism. In fact, he argued that governmental intervention was needed to keep economic inequalities in check. He also advocated breaking up monopolies, providing public works such as roads and bridges, and educating the middle classes.

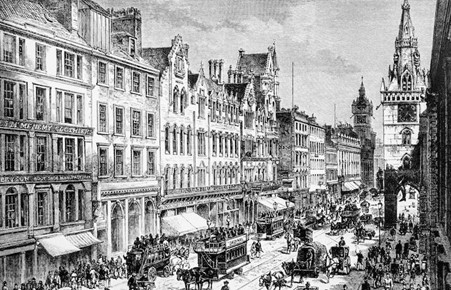

Trongate, one of Glasgow’s oldest streets, during the late 18th century

De Luan/Alamy

3. He was the first Scot ever to appear on an English banknote

Between 2007 and 2020, Smith featured on English £20 banknotes. He was a proud Scotsman, a Kirkaldy native who spent his formative years in Glasgow.

Following Scotland’s 1707 union with England, Glasgow was asserting its place as a wealthy city of merchants. The city was benefiting from access to Britain’s growing trade empire, and by the 1740s it had become the centre of a thriving trading network with North America and the Caribbean.

At the University of Glasgow, Smith taught the sons of wealthy sugar and tobacco merchants and slave-labour plantation owners. They dominated local politics, invested their money in shipping and new industrial development, and were rebuilding Glasgow into an imposing city of stone.

4. He was a polymath

In his Glasgow classes, Smith lectured on moral philosophy, a broad humanities subject, which in 18th-century Scotland included topics as varied as morals, politics, religion, economics, jurisprudence and history.

He reworked some of these university lectures into a successful book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Published in 1759, this made him a household name throughout Europe.

Today, the book is mostly remembered by historians. But Smith believed his main achievement was teaching young Scots how to live a good, ethical life. Toward the end of his life, he wrote to the principal of the University of Glasgow that his 13 years as a professor of moral philosophy had been “the happiest and most honourable period” of his life.

5. His legacy is controversial

Smith’s economic theories have inspired a long line of free-market economists, but they also influenced Marx’s critique of capitalism. Marx admired Smith’s attempts to analyse the new modes of production that were emerging in early industrial Britain, as well as his innovative theory that wealth was related to labour.

Even today, Smith’s legacy is claimed both by neoliberals (who emphasise his defence of free trade) and by leftwingers (who emphasise his views on the pitfalls of capitalist economies). But Smith would have been puzzled by modern attempts to classify him as either of the right or the left. He was merely studying the changing world in which he lived: an early industrial society that was increasingly engaged in colonialism and global trade. It is time to reclaim Smith’s legacy from economists and to celebrate him as an astute observer of Europe’s emerging modernity.

Anna Plassart, Senior Lecturer in History, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Contact our news team

For all out of hours enquiries, please telephone +44 (0)7901 515891

Contact detailsNews & articles

The FUNdamentals: Why fun matters more than we think

In a world that feels increasingly serious and pressured, fun can seem like a guilty pleasure — something optional, even frivolous. But what if fun isn’t an add on at all? What if it’s essential?