Meeting the growing demand for electrical vehicles

Electric cars are set to dominate the market by 2035. Decarbonising transport will be a big step to meeting global climate targets and the UK has proposed a ban on the sale of new petrol vehicles by 2030 to help the transition to electric cars. Consumers are keen to make ethical choices and the improvements in electric vehicle (EV) performance have already seen many make the switch: electric cars accounted for 14% of global sales last year and this figure is projected to rise to 18% by the end of 2023.

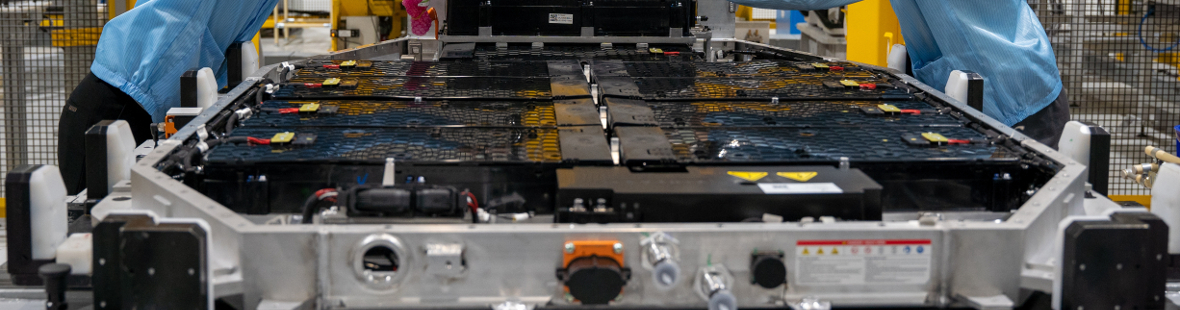

This shift in customer behaviour is driving a massive demand for EV batteries – a special subset of lithium-ion batteries which also contain the metals nickel, manganese, and cobalt. The supply chain to source and mine these metals has many serious ethical and sustainability issues, particularly in the global South, which are often overshadowed by the focus on reducing carbon emissions.

"Electrification of vehicles is vital to help achieve sustainability, climate targets, and a green energy transition. [But the] batteries they rely on create complex global supply chains that have many unsustainable externalities," explains Michael Pryke, an economic geographer at The Open University. "Communities [in the] global South [are hugely] affected by the extraction of critical minerals used in battery technologies [but the] UK public [is largely unaware] of what is involved in meeting the growing demand for EVs."

Supported by the Open University's Open Societal Challenges programme, Pryke and an international interdisciplinary team are hoping to tackle the complex social issues present throughout the supply chain – including researchers from Europe to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Chile, and Australia. The team, whose research interests span from chemistry to philosophy, engineering, and politics, will begin by mapping the stakeholders across the lithium-ion battery supply chain, analysing the geopolitics and power relations shaping the process and identifying the key challenges at each stage. "Interdisciplinarity is at the core of our activities because previous approaches have focused on technological solutions to battery design and recycling," says Pryke. "While useful, they lack a full understanding of how the political economy of global supply of battery minerals operates and a clear sense of what a ‘just’ and ‘sustainable’ supply chain looks like which is crucial if we are to generate sustainable solutions beyond the localities where the EV technology is adopted."

Community perspectives will be a key aspect of this project and the team will work alongside communities in Chile, Argentina, and the Democratic Republic of Congo to examine the supply chain from a local standpoint. The insights gained from this work will highlight gaps in international and national legislative frameworks and ultimately inform changes to environmental regulation, protecting the interests of local people. "[We will also be producing] short videos done in situ at mining sites and the homes of affected communities to capture and share their (and their families’) unique take on the supply chain and their thoughts on how it could be enhanced," says Pryke. "[This will be one of many resources created] to engage research, … policy, … and private sector communities, … better public understanding, and … [ultimately] hold multinational enterprises to account."

Increasing public awareness is an important goal for the team and following this work they will produce a collection of educational resources for secondary schools, in addition to a freely-available adult course on the Open University’s OpenLearn portal.

"[We want] to develop and help embed a sustainable and ethical electric vehicle battery supply chain [and a big part of this is creating] a step change in consumer preferences," comments Pryke. "[But] our focus is around International Development [so we’re also aiming to ensure] government and industry actors ultimately accept social and environmental responsibility for effecting a more ethical supply chain."