Methane on Mars: a new discovery or just a lot of hot air?

The discovery of life on Mars would get pretty much everyone excited. But the scientists hunting for it would probably be happy no matter what the outcome of their search – whether life turned out to extinct, dormant or extant. They’d even consider finding no evidence of life whatsoever to be an important discovery. But, as the saying goes, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and it will take many decades of detailed exploration of Mars to be reasonably sure that life has always been absent there.

There have been no direct observations of living organisms or fossils on Mars so far. But there are other types of evidence. One of the most often cited is the controversial detection of methane in the planet’s atmosphere, first in 2004 and then in 2014. This could have been produced by some kind of past or present microbial lifeform. However, the abundance is so low that the data remain uncertain. And in 2018, the team behind the European Space Agency’s Trace Gas Orbiter said they had failed to discover any methane.

Now a new paper, published in Nature Geoscience, reports a fresh detection of methane in the planet’s atmosphere, along with a theory of where it came from. But given how difficult it is to make reliable measurements of this gas, how confident can we be about the results?

Double detection

The new research used archived data acquired between 2012 and 2014 by the Planetary Fourier Spectrometer aboard Mars Express, which studies the composition of the planet’s atmosphere through the infrared radiation that is reflected and emitted by the planet. This is the same instrument that first detected low levels of methane in Mars’ atmosphere in 2004.

The difference between the two sets of observations comes from the mode in which the spectrometer operated. In 2004, the data were acquired by the instrument looking through the atmosphere to the surface as Mars Express orbited the planet. In the new study, the instrument was pointed at a single surface feature, and tracked the feature as the spacecraft orbited.

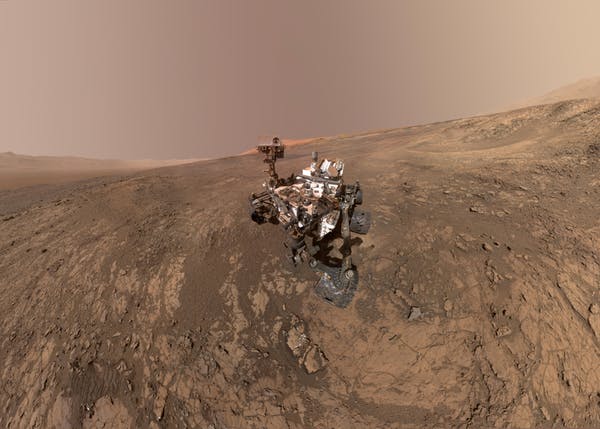

Curiosity at Gale Crater.

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

The significance of the data arises from the feature that the team selected to track: the Gale Crater. This, of course, is the site where the Curiosity rover is operating – and where the Tunable Laser Spectrometer on board Curiosity detected elevated levels of methane in 2014.

The spectrometer on Mars Express was tracking the Gale Crater before, during and after Curiosity’s detection. Excitingly, it also detected elevated levels of methane in the region – the first time that a simultaneous detection of methane at the surface and in the atmosphere has occurred. This, perhaps, makes the new measurement more reliable than the previous detections.

The researchers also attempted to pinpoint the source of methane using a grid-mapping technique. They created computer models of emission scenarios in each grid and also looked at geological features in each place to see if there were potential sources of methane. They inferred that the methane was released from a region to the east of Gale Crater and that the most likely origin of the gas was seepage of along faults in ice beneath the surface.

Finding where the methane came from is only a stage in determining how it formed. Importantly, there are many mechanisms other than living organisms that could have produced it, for example geological processes. For example, a geological event may have fractured the ice containing bubbles of methane to release it into the atmosphere.

But the new study does not attempt to make any conclusions about the origin of the methane. However, the authors do comment that their findings, especially in corroborating the Curiosity data, suggest that the methane release is more likely to be by small, short events, rather than episodic large exhalations. Indeed, it could be speculated that small events are more likely than large ones if Mars turns out to experience the “marsquakes” (similar to an earthquake) that the Insight mission is programmed to detect.

So whatever the source, it does seem there may be methane on Mars after all. However, we’ll need further confirmation to be completely sure. Fortunately, fresh findings are most likely to be available soon. The team that failed to discover methane with the Trace Gas Orbiter has been analysing new data for several months.

As it has an extremely sensitive detector for methane on board, it is anticipated that continued data collection over the next few years will give a much better picture on whether there is a seasonal, or an episodic variation in atmospheric methane. Or it could reveal that it is just an illusory will-o-the-wisp.

Monica Grady, Professor of Planetary and Space Sciences, The Open University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Quarterly Review of Research

Read our Quarterly Review of Research to learn about our latest quality academic output.

Contact our news team

For all out of hours enquiries, please telephone +44 (0)7901 515891

Contact details