You are here

- Home

- Day 229, Year of #Mygration: Critical Race/Religion Readings of ‘White Crisis’ in Science Fiction Dystopia

Day 229, Year of #Mygration: Critical Race/Religion Readings of ‘White Crisis’ in Science Fiction Dystopia

In today’s post, OU Lecturer Dr Syed Mustafa Ali traces the history of 'White Crisis' and reminds us of the importance of being open to diversity in today’s globalised world. Dr Ali's research focuses on the social, political and ethical aspects of computing and ICT – more specifically, the interrogation of computational, informational, cybernetic, systems-theoretical, and Trans-/Post-human phenomena from a perspective informed by phenomenology, critical race theory and postcolonial/decolonial thought.

In October of last year, I attended the screening of director Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049, the long-awaited sequel to Ridley Scott’s dystopian science fiction classic, Blade Runner (1982). Hampton Fancher co-wrote both films and inspired by Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968).

In what follows, I briefly explore a critical race/religion theoretical reading of an extended scene – in fact, the longest – from Villeneuve’s film. I want to consider the possibility of interpreting this scene as a metaphor for the historically-recurrent phenomenon of ‘White Crisis’ that is arguably manifesting in the contemporary era in such phenomena as Brexit, the rise of the Far Right in Europe, and the election of Trump. Such phenomena need to be understood in relation to concerns about the migration of the non-white/non-Western ‘other’ from the periphery of the modern/colonial world system into its Western core, and I suggest that this ‘other’ is usefully understood in relation to another ‘other’ in Dick’s novel and Scott’s and Villeneuve’s films, viz. the figure of the ‘replicant’.

To proceed, I need to state what I take to be the key problematic engaged by the novel mentioned above and films, and that is an exploration of what it means to be human in the context of a world within which it has become possible to create synthetic humanoid lifeforms. The replicants mentioned above (androids in Dick's novel), – that are largely indistinguishable from human beings, both regarding physical appearance and behaviour. Insofar as ‘the human’ as an anthropological category can be shown to have a history within Europe/‘the West' that is, thoroughly entangled with religion cum race (Wynter 2003) (Lloyd 2013) it follows that Blade Runner and its replicants readily lend themselves to being interrogated and/or mobilized along racial lines.

What if, for example, the dystopia that is Blade Runner simultaneously depicts a white utopia in the sense that it functions as a veritable ‘call to arms' to maintain global white hegemony? In short, what if Blade Runner can be read as a liberation narrative, but might also be interpreted as re-affirming domination? Engaging this possibility takes me to the scene in Blade Runner 2049 that has inspired this piece – ‘Sea Wall’. Briefly, this involves a long physical struggle to the death between two replicants, male LAPD cop (‘blade runner’) Agent K and female right-hand of Niander Wallace, Luv, set against the backdrop of a rising flood of water in the Sepulveda Sea Wall. According to an entry on Off-World: The Blade Runner Wiki (Off-World n.d.),

Due to the rising oceans in the world of 2049, Los Angeles faced flooding and eventual annihilation without some way of stopping the sea levels from affecting the city. Thus, the Sepulveda Sea Wall was constructed to prevent this catastrophe. It resembles a mix of large, defensive fortifications of the past combined with more modern dams on an immense scale.

The same entry also states that:

On the way to the Off-World colonies to torture [human fugitive blade runner Rick] Deckard on the whereabouts of his child and the location of the replicant resistance movement, Luv and a couple of escort spinners fly above the sea wall towards LAX, now a spaceport. K intercepts them and shoots down all three vehicles, and engages in a fight with Luv when her spinner crashes where the wall meets the ocean … The waves nearly destroy the spinner and drown Deckard until K finally overcomes and kills Luv, saves Deckard, and swims back to the base of the wall before taking Deckard to his daughter.

I want to draw attention to two things here:

First, the naming of the sea wall as the Sepulveda Sea Wall which, from a critical race/religion perspective, points us to the figure of Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda (1494-1573 CE), a Spanish Renaissance humanist, philosopher, theologian, and proponent of colonial slavery. Sepúlveda’s importance lies in his position in the infamous Valladolid debates of 1550-1551 CE, where he argued against Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas that the ‘New World natives’ encountered by Columbus in 1492 CE were not humans, but rather animals and therefore should be treated as chattel. The relevance of the Valladolid debates lies in their entanglement with the transition from ‘religion’ to ‘race’ (proper) as a means by which Christians cum Europeans cum ‘Westerners’ were to establish and police the line/boundary/border of the human – the issue of borders clearly being of central importance to contemporary debates about migration and its limits. Which leads me to ask whether the Sepulveda Sea Wall, the function of which is to hold back the rising sea levels and stave off the possibility of flood, has been so named, intentionally or otherwise; with a view to its functioning as a metaphor drawing attention to the need for the extant (white) power structure to once again push back against the ‘dark hordes’, the ‘barbarians at the gates’ as it has attempted to do in past ages. In this connection, it is rather telling that the entry on the Blade Runner Wiki states that the wall “resembles a mix of large, defensive fortifications of the past combined with more modern dams on an immense scale [emphasis added].”

This metaphor, in turn, leads me to my related second point which concerns the phenomenon of ‘White Crisis’. Anxieties about the future (or otherwise) of whiteness are arguably traceable to the late 19th and early 20th century phenomenon of ‘White Crisis’ explored by Füredi (1998) and Bonnett (2000, 2005, 2008), the latter of whom refers to a decline of overt discourses of whiteness – more specifically, white supremacism – and the concomitant rise of a discourse about ‘the West’.

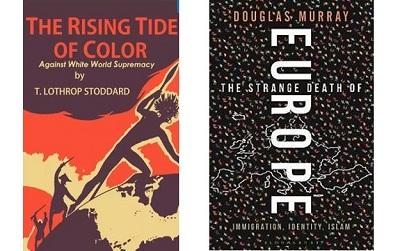

Examples of such periodically manifesting ‘White Crisis’ discourse include Lothrop Stoddard’s alarmist The Rising Tide of Colour: The Threat Against White World Supremacy (1920), Ronald Segal’s more ambivalent The Race War (1966), and in the contemporary ‘post-racial’ era, Douglas Murray’s The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam (2017). Commenting on the emergence of ‘White Crisis’ literature in late 19th - early 20th century Britain, Bonnett (2003) maintains that “the period when ‘the white race’ was represented as undergoing a grave crisis was … also the period when white supremacism was most fully and boldly incorporated within public discourse [emphasis added].” Crucially, according to Bonnett, “this relationship is unsurprising, for the one is the flip-side of the other.” (p.322) I’m inclined to think that this ambivalent “glass half-full, glass half-empty” approach to thinking about whiteness is usefully extended to reading Blade Runner, viz. as both critiques of whiteness and its affirmation.

In this connection, I want to suggest that the recent election of Donald Trump as President of the United States, the Brexit phenomenon in the UK, and the continued rise of Far/Alt-Right politics in the US and Europe can, – and should, – be seen as one response to the re-emergence – or rather ‘re-iteration’ – of the phenomenon of ‘White Crisis’. It is almost fifty years on from the anti-racist struggles of the 1960s, and almost a century on from when ‘White Crisis’ was first being discussed in the West (specifically, Britain and America). Crucially, Bonnett (2008) maintains that “whiteness and the West ... are both projects with an in-built tendency to crisis. From the early years of the last century ... through the mid-century ... and into the present day ... we have been told that the West is doomed.” (p.25)

In concluding, I want to return, like the ocean tide, to what motivated this piece, viz. a consideration of sea walls and rising tides. Joining the dots on the basis of what has been stated above, I suggest that Blade Runner 2049’s long scene at the sea wall – the Sepulveda Sea Wall, built to hold back the rising sea levels – should be understood as a metaphor for contemporary concerns associated with the latest manifestation of ‘White Crisis'. Concerns about ‘rising tides of colour’ as peripheralised non-white/non-European/non-Western people once again attempt to migrate into the core of the modern/racial world system as refugees, asylum seekers and for a variety of other reasons. Insofar as the modern/colonial system was forged in violence against the periphery, and has been maintained, expanded and refined on the same basis, such migration needs to be understood, at least partly, in terms of ‘blowback', of return from the periphery to the core.

An ebb and a flow, like the rising tide against the sea wall.

Quarterly Review of Research

Read our Quarterly Review of Research to learn about our latest quality academic output.

Contact our news team

For all out of hours enquiries, please telephone +44 (0)7901 515891

Contact details