You are here

- Home

- Open Research

- Helping with your open research

- Open Research in Artificial Intelligence: A personal account of the long view

Open Research in Artificial Intelligence: A personal account of the long view

By Dr Paul Piwek, School of Computing & Communications.

Having worked in Artificial Intelligence (AI) for over 30 years, Open Research Week at The Open University seemed like a good occasion to reflect on the role of Open Research in my own AI research. Though this is first and foremost a personal perspective, it is, of course, impossible to do so without reference to where we are now, after the 30 November 2022: the day OpenAI released ChatGPT and AI became a daily topic of discussion in the mainstream news.

What I hope to do here, is to illustrate some of the trends in AI research over the past decades from my own experience and provide some context for those recent developments. If anything, the take-away message is that there is no research without open research – both from a practical and an ethical point of view.

Generative AI and the ideal of flexible information presentation

With the release of ChatGPT in 2022, public awareness of AI or, more precisely, Generative AI, has dramatically grown. And it is not just awareness that is growing: Generative AI is now used in many real-world settings ranging from coding and data analysis to advertising.

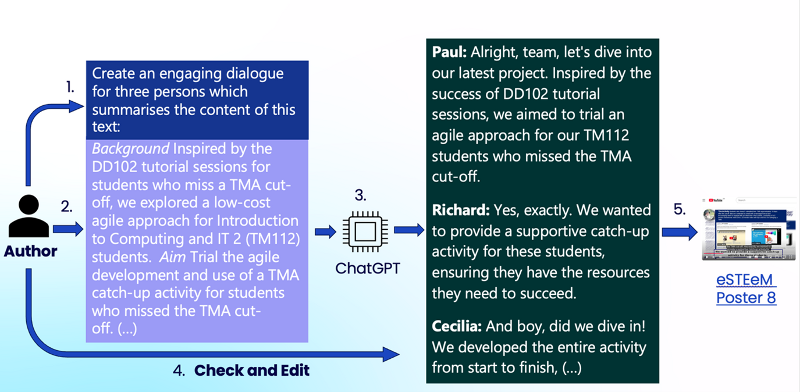

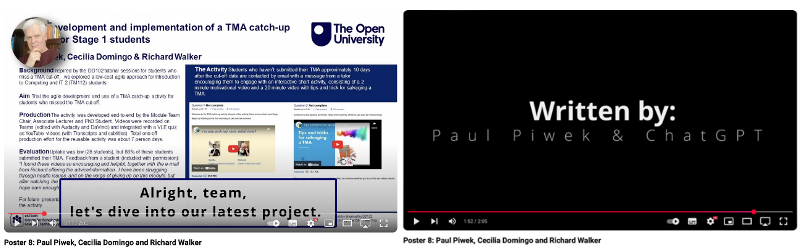

Let me give an example of one use of Generative AI which has excited me and ties in with my own practice as a researcher. As researchers, we share our work at conferences. About a year ago, with my colleagues, Cecilia Domingo and Richard Walker, I got to present a poster at the annual STEM scholarship event at The Open University. The organisers requested that each poster presentation was accompanied by a short online video presenting the work. Typically, such a video involves the researchers talking to camera and explaining their work. But we wanted to do something different. So, we wrote a 150-word summary of our research and asked ChatGPT to turn it into a script, a bit like a film script, for a conversation between the three of us.

Using the ChatGPT generated script, we then recorded the conversation and Cecilia created a video from the result. These steps are illustrated in Figure 1. The final product is the video (we included a couple of stills in Figure 2) – it can’t have been that bad, because that year it was voted the best poster presentation by the conference participants. ChatGPT helped us present our research in an accessible and engaging way.

It’s worth emphasising two things: Firstly, though we enlisted the help of ChatGPT the original content was ours and we checked ChatGPT’s film script didn’t misrepresent it. That took only a minute or so, but we did have to correct a couple of sentences where ChatGPT was “hallucinating” things. Additionally, we felt that it is important to be transparent when using such technologies, so we made sure to include ChatGPT in the credits.

Why bring up this example? In 1998, fresh out of my PhD examination, I joined the Information Technology Research Institute (ITRI) in Brighton which had a thriving research programme around “flexible information presentation”.

Finding the best ways to present information

The use of ChatGPT that I just described is a good illustration of flexible information presentation. The idea is that with the right technology, the same piece of information can be presented in many different ways, depending on the context and audience. For instance, sometimes information is conveyed best by a written text with an appealing layout and perhaps some pertinent illustrations, whereas in other situations spoken words with the right prosody are required. And in some circumstances, presenting information as a conversation or dialogue can be more engaging and informative than a monologue.

By around 2000, I had started to research one particular variety of flexible information presentation: the generation of dialogue scripts. As a research fellow, I worked on Net Environment for Embodied Emotional Conversational Agents (NECA), a project with the German and Austrian Research Institutes for AI (DFKI and OEFAI) and an Austrian AI company. This project, led in Brighton by Kees van Deemter, developed, among other things, a demonstrator in which two salespersons discuss cars (environmental friendliness, economy, etc.) based on handcrafted AI knowledge representations of car properties. Watching such a conversation was meant to make potential car buyers make more informed decision, whilst also being engaged (see Figure 3).

The Text to Dialogue (T2D) system

By 2005, when I joined The Open University, and following on from the NECA project, I had become deeply interested in AI technologies for dialogue script generation. So far, in NECA we had been generating dialogue from knowledge representations that had to be handcrafted for each and every new topic of discussion. To get around this problem, I decided to start working on generating dialogue scripts from text in monologue form. There is an abundance of text, especially, online text. An AI technology that could transform such text into dialogue scripts could be used to generate dialogues on virtually any topic. During a three month visit to the National Institute of Informatics (NII) in Japan – working with Helmut Prendinger and his team - we developed an AI system for automatically generating dialogue from monologue, the Text-to-Dialogue, or T2D, system.

With text as input, rather than a specific knowledge representation, we had the technology to generate short dialogue scripts on virtually any topic – unlocking the information from text in monologue form. However, the algorithm for doing so was still handcrafted, as in NECA, and therefore based on us finding good rules for turning monologue into dialogue.

From handcrafted to data-oriented AI

The use of handcrafted algorithms and rules was a common approach around 2006, especially in language generation, though the general trend was to move away from handcrafted rules to learning from data.

This is what my next project, CODA “Coherent Dialogue Automatically generated from dialogue”, aimed for. To do so, we collected dialogues, wrote the corresponding monologue and then used an algorithm to learn the relation between the two. Our system learned from philosophical dialogues and monologues. However, once it had learned the relation between monologue and dialogue, it could then be used to produce dialogue on any text.

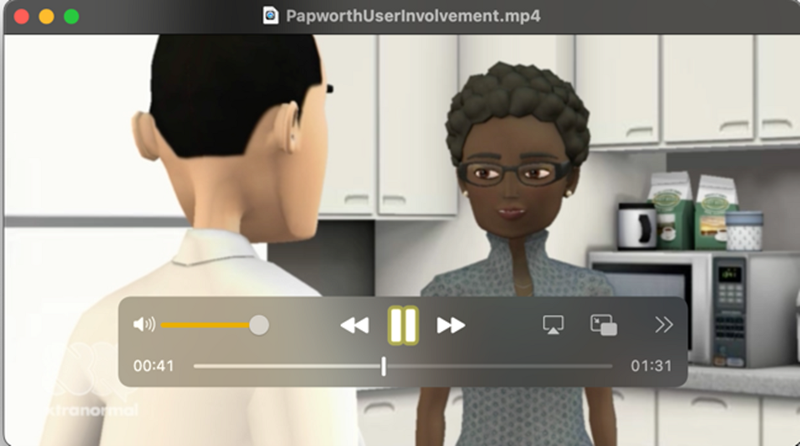

At the time we were commissioned by the Papworth Trust, a charity for assisted living, to turn their information leaflets (Figure 4) into short videos. We used the CODA technology to first create the dialogue scripts. For instance the leaflet in Figure 4 resulted in a script that included the following text:

R: It is important that we listen to the people using our services.

U: Why is it important?

R: Because this will help us understand the changing needs of our service users.

We offer training and development to people who get involved. (…)

To create videos for computer-animated characters from these dialogue scripts, we used a tool by a company called Xtranormal later succeed by Nawmal (see Figure 5). The CODA dialogue videos were embedded on the Papworth Trust website from 2009 to 2019.

The CODA research project was an instance of Open Research in two important ways: we shared the code for mapping monologue to dialogue as well as the collection of dialogues and monologues which we used to learn these mappings. Originally, to share such resources, we used our project website, but more recently we starting using the Open University’s Open Research Data Online (ORDO).

Comparing CODA with today’s Generative AI, there are several key differences. Our collection of dialogues and monologues contained thousands rather than billions of words on which current Generative AI systems are trained. However, though small, as I will explain, CODA compares positively with OpenAI in that it was more open and transparent

We sourced the CODA dialogues from the Gutenberg library, which contains out-of-copyright texts. Among the CODA dialogues are extracts from a wonderful book by Mark Twain 'What is man?' which is entirely in dialogue form. Each dialogue was paired with a monologue that expressed the same information – the research team wrote these monologues. We released all these texts in full, allowing other research teams to build on the work.

Contrast this with OpenAI, which has held back from sharing the exact details of the texts they are using to train their AIs and are mired in several ongoing copyright court cases. Whereas using copyrighted materials without permission has both ethical and legal implications, not sharing the details of the texts that are used and the algorithms to process them is counter to the idea of Open Research.

In "Googleology is Bad Science", the late Adam Kilgarriff warned researchers against using commercial search engines to collect web data for a variety of reasons, but perhaps most importantly because their operation is not transparent and doesn’t lead to reproducible science: today’s search results for the same terms can be completely different tomorrow for unknown reasons.

In the same spirit, “GPTology is Bad Science” because we don’t have access to the complete methods, algorithms and data used by the various incarnations of OpenAI’s GPTs. Science will peter out if researchers can't build on and reproduce each others' work. Or in the words, used at one time by Newton: “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.”

Coming back to CODA, we evaluated the system comparing it with the Text to Dialogue system (T2D). When we asked human raters to score the dialogues, we found CODA to produce better dialogues than T2D. This result is consistent with the move away from handcrafted rules to systems that learn. And this brings me to the final topic of this post: the evaluation of AI systems.

Shared tasks and evaluation campaigns

Much work in AI up to 2010 involved individual research groups building a system and then providing a report on how well it did. Those reports, though useful, could be difficult to interpret, since there was no direct objective comparison with previous work. It became clear that progress could be enhanced by research teams working on the same tasks and comparing results.

In 2010, with CODA team member Svetlana Stoyanchev and Brendan Wyse, who was studying for his computing MSc at the time, we co-organised the First Shared Task and Evaluation Campaign on Question Generation.

Question Generation was of interest to the CODA team, because it is an integral part of dialogue generation. Dialogue generation itself was a task that would be too specialist and niche to attract sufficient participants. At a National Science Foundation (NSF)-sponsored Question Generation workshop, I decided to propose a task that had a broad appeal and a low hurdle to entry: the generation of questions from single sentences. For instance, given the sentence “The poet Rudyard Kipling lost his only son in the trenches in 1915” (extracted from OpenLearn), systems were to generate questions of various types:

- Who: Who lost his son in the trenches in 1915?

- When: When did Rudyard Kipling lose his son?

- How many: How many sons did Rudyard Kipling have?

The Question Generation Shared Task and Evaluation Campaign took place in 2010 at Carnegie Mellon University as part of the Intelligent Tutoring Systems conference and the 3rd Question Generation workshop and turned out to be a success - the task of generating questions from single sentences attracted five teams from across the globe (Germany, India, US and UK). One striking finding was that, regardless of which system produced a question, we found a correlation between the quality of questions and the source of the input text. Questions from OpenLearn were better than those from Wikipedia and those in turn were better from sentences extracted from Yahoo!Answers. Since the editorial oversight was less stringent from OpenLearn to Yahoo!Answers, this suggests that high quality sources provide better results.

Concluding remarks

Question and Dialogue Script Generation, as specific tasks for AI systems, had their origins around 2000 and have since then come of age. Current Generative AI does remarkably well on these tasks, at a level that makes it useful for practical applications, as we saw at the beginning of this paper.

Our description of several past projects in this space highlighted several trends:

- a move away from handcrafted knowledge representations and algorithms to systems that learn from data, resulting in better and more scalable systems

- a move away from explicit knowledge representations to the use of raw text as input and output to AI systems

- a move to the adoption of shared tasks and evaluation competitions to drive research forward

Current Generative AI exemplifies each of these points. Shared Task and Evaluation Campaigns persist as today’s benchmarks and leaderboards for Generative AI systems. And yet, there are also concerns: Open Research depends on sharing code and data. Unfortunately, much of the cutting-edge work is far from transparent: data sources are not disclosed or only partially, and descriptions of underlying code and training techniques are incomplete. Having said that, there are exceptions. For instance, Hugging Face’s SmolLM2 outperforms Meta’s Llama3.2 on some leaderboards and yet, in contrast with Llama3.2, for SmolLM2 the training data set has been described and shared in full detail in the spirit of Open Research.

Open Research is a community activity in which researchers both build on each other’s work and compete with each other. Last but not least, Open Research is not only essential for scientific progress, but can also be personally fulfilling; in the words of Brendan Wyse, who co-organised the 2010 Question Generation Shared Task and Evaluation Campaign and was completing his Computing MSc at the time:

As a part time, mature student with no experience of the open research community it was very daunting for me to enter that domain and start contributing. But, I found the whole community very welcoming and encouraging and my confidence in presenting and public speaking went to levels I never thought possible.