The UK might have accepted the idea of youth mobility with the EU, but it’s not happening any time soon

The UK might have accepted the idea of youth mobility with the EU, but it’s not happening any time soon

The language might be dry, but the political shift is significant. Monday’s summit between the UK and EU leaders in London resulted in an acknowledgement of the “mutual interest to deepen our people-to-people ties, particularly for the younger generation”.

This announcement is an important step forward in the creation of a youth mobility scheme between the EU and UK, even if it has required a name change to become a “youth experience scheme”. It is the first time that a British government has formally accepted this as something to negotiate and implement.

However, there is scant detail about how it will work in practice and what the inevitable limits will be. While the permitted activities (“work, studies, au-pairing, volunteering, or simply travelling”) seem extensive, they are prefaced with the dreaded words “such as” – which means no one has actually agreed any of it.

It was clear over a year ago that the basic models that the two sides have for youth mobility differ. The EU wants lengthy exchange periods and home tuition fees for students; the UK wants shorter stays, caps on numbers and retention of international fees for EU students at UK universities. The achievement of a deal would require at least one of them to move. This week makes this difference now the formal position, rather than showing whether movement is possible.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

It’s possible that discussion of British participation in the Erasmus+ scheme for student mobility might be a partial stopgap, making exchanges within study programmes easier. However, the ambition for creating those deeper people-to-people ties will need more to make it meaningful.

As the troubled history of this idea should indicate, there’s still a very long way to go before anyone gets to use the scheme in practice.

The founding irony of a youth mobility scheme with the EU after Brexit is that it was originally a British idea. It was produced under Rishi Sunak following his conclusion of the Windsor Framework on Northern Ireland, when he was looking for areas to rebuild ties with Europe.

In 2023, feelers had been put out to various EU member states about concluding bilateral deals with the UK. While there was some interest, the general feeling was that this was best handled at an EU level, to avoid any cherrypicking of countries by London.

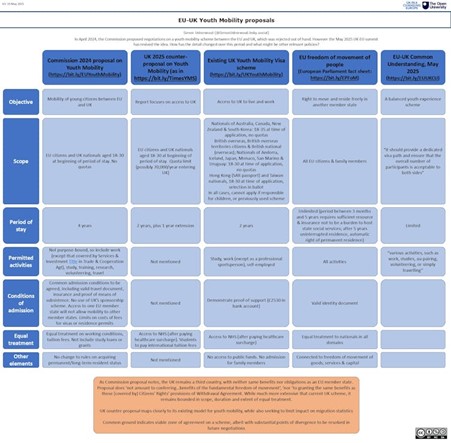

A summary of UK-EU youth mobility proposals

Simon Usherwood, CC BY-NC-SA

In April 2024, the European Commission produced an ambitious proposal for a scheme. It put forward that 18- to 30-year-olds would be able to get a visa for up to four years for any purpose – work, study, travel – without quotas on numbers.

Both the Conservative government and the Labour opposition had rejected the proposal out of hand. This was partly out of concerns over the potential impact on immigration figures and on student finances: the commission suggested EU students should be able to pay UK university fees. Mostly, however, it came from a desire not to be seen to make a big agreement with the EU that looked a bit like freedom of movement.

To be clear, youth mobility is very much not freedom of movement. The latter implies no limits on entry, length or purpose of stay, as well as access to any kinds of public services as if you were a resident national. The former still means paying for a visa and strict limits on those services. But such legal points remain rather marginal in the British political and media debate.

Since last year, there has been some to and fro, but largely behind closed doors and with the incoming Labour government continuing the line that such a scheme wasn’t on the cards. While the UK has a number of youth mobility schemes with countries around the world, these are typically limited by quotas and time (normally to two years) and require the person to be working or studying.

Moving on?

On the British side, Home Office concern about immigration figures is clearly still critical, especially in the context of the recent white paper that aims to cut back migration. Universities too have been vocal about the financial impact of losing tuition fee income from EU students.

But on the EU side, the matter is seen very differently. To some extent, the interest is in maintaining the links with the UK, especially for young people that could gain from experiencing more of how their neighbours live. But much more than this is the sense that youth mobility has become something of a test for the British government.

Labour’s return to office last July marked the unleashing of a significant diplomatic effort to engage with European counterparts and to talk up the value of working together. Youth mobility is a test of that value for some in European capitals, both in terms of being able to negotiate an agreement and of being able to sell it to the British public.

The coming weeks and months will therefore be a key period if the reset is to result in more sustainably improved relations. Even if the basic shape of UK-EU relations isn’t about to shift, the ability for both sides to be able to talk and act constructively will still matter in delivering from that long list of summit ambitions.

Simon Usherwood, Professor of Politics & International Studies, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Contact our news team

For all out of hours enquiries, please telephone +44 (0)7901 515891

Contact detailsNews & articles

Foraged mushrooms and sea beet featured in British meals in the 16th century. Why not today?

Wild garlic, oyster mushrooms and sea beet were once regularly gathered and eaten as part of meals across the UK. Today, some people have concerns about eating food growing in the woods or hedgerows, but are keen to discuss why – as our research shows.