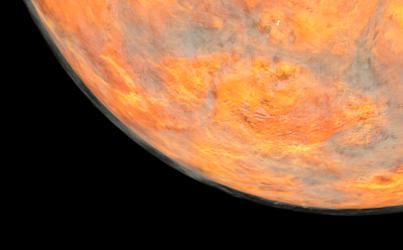

OU Astrochemistry facilitates research that signals life on Venus

An international team including an OU academic have made a surprising detection of a rather unusual molecule – a rare gas called phosphine - on Venus.

Astronomers at the OU were able to participate in the study because the OU has invested over the last four years as a minor consortium partner in the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT), showing that even small research investments by the OU can pay big dividends.

Dr Helen Fraser, Astrochemist and Senior Lecturer in the OU’s Faculty of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics, is part of the international consortium that has made this landmark discovery that could point to extra-terrestrial ‘aerial’ life on the planet.

The team, led by Professor Jane Greaves of Cardiff University, has detected a rare gas – phosphine – in the clouds of Venus, which has just been reported in Nature Astronomy.

They initially made the discovery using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in Hawaii. Thereafter, they confirmed the research findings using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. Both facilities observed Venus at a wavelength of about one millimetre, much longer than the human eye can see – only telescopes at high altitude can detect this wavelength effectively.

Dr Fraser, said:

“We have scratched the surface of something really exciting. By combining our expertise as chemists, astronomers, biologists and geologists, we move ever closer to answering the question: is there life in the universe? And, perhaps even more tantalising, is there life beyond Earth in the Solar System?”

The OU is one of very few UK universities where both observational and laboratory astrochemistry are active research activities, enabling OU researchers to benefit from the synergies between astronomy “in the lab” and “at the telescope”. Dr Fraser’s three astrochemistry labs were opened in 2013 by Professor Ewine van Dishoeck, who in 2018 won the Kavli Prize for Astronomy for her pioneering work in observational and laboratory astrophysics. The most recent permanent member of academic staff in the School of Physical Sciences, Dr Anita Dawes, also leads a research team that conducts experiments recreating conditions in space. These labs have made it possible for Dr Fraser and Dr Dawes to unravel some of the many chemical puzzles that result from observations of chemicals on other planets, or where new stars and planets are forming.

Dr Fraser added:

“On this occasion though, it was the observational astrochemistry that was key. The discovery of phosphine, by the team’s own admission, was somewhat unexpected and serendipitous, and to date, though thorough chemical modelling, it really does seem that the only likely origin of the phosphine is biological.”

For OU researchers this is good news; it means a swathe of laboratory experiments are now needed to try and understand how the phosphine can be generated, and our leading expertise in astrochemistry, coupled with the astrobiology knowledge of AstrobiologyOU led by Professor Karen Olsson-Francis will no doubt be invaluable in that quest.

Contact our news team

For all out of hours enquiries, please telephone +44 (0)7901 515891

Contact detailsNews & articles

OU researchers lead international advances in planetary protection

Open University researchers are leading international advances in planetary protection, helping ensure that space exploration is safe, sustainable, and scientifically rigorous.