Day 41, Year of #Mygration: Navigating Refugee Smartphones and Maps

By Marie Gillespie, Professor of Sociology, The Open University, @MarieBGillespie.

By Marie Gillespie, Professor of Sociology, The Open University, @MarieBGillespie.

While researching how smartphones are used by refugees on their journeys, as part of an Open University multidisciplinary research project, we were shown a map by one of our interviewees that we now know thousands of refugees have used on their journeys. It was circulated widely among Syrian and Iraqi refugees during 2015-16 – before the Balkan route was closed. It was circulated on WhatsApp mainly. At the time, this was the preferred means of communication among refugees because it was encrypted and therefore safer to use in terms of safeguarding privacy and avoiding surveillance by the authorities than Facebook.

The Road to Germany on WhatsApp

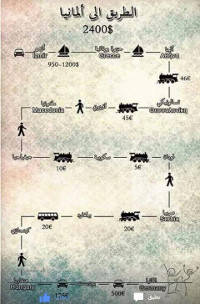

The title of this image in Arabic is “The Road of [to] Germany”. It shows place names in Arabic, English and Greek. These are the translations the country and city names on the route: Izmir to Greek Island to Athens to Thessaloniki to Evzonoi [Evzoni] to Macedonia to Gevgelija to Skopje to Lojane to Serbia to Belgrade to Kanjiža to Hungary to Budapest to Germany. The cities which are featured on the map are either capital cities or border towns. The information is succinct, so as to help refugees get to the best place for them to make the various crossings they need to make.

It shows the cost of the whole journey from Izmir in Turkey to Germany as 2,400 American dollars. The price tag for the sea crossing to the Greek Island is in dollars, while everything that follows is in Euros. This can be read as a warning: those following the map must take currency into consideration. It also indicates the means of transport and cost of each leg of the journey in the local currency, as well as those parts of the journey that refugees need to make by sea, by car, by train and on foot.

We do not know who the original creator/s of the map were but whoever designed it had in- depth knowledge of the journey and was very careful to give precise details. It is elegantly simple and its creators were meticulous in providing all the most essential information. For example, in translating place names they have taken great care so that those using the map would be able to pronounce the names of the places they needed to get to. The translators also wanted to make sure the names were spelt as accurately as possible to avoid any confusion.

The graphic detail is attractive. The figures of the ships and trains suggest that someone with graphic design and digital skills took time to put this together. But we can also see the stick figures at the bottom, jumping for joy. These were added to a hard copy that was later scanned and passed on to another refugee. This map has had its own social media life. It has had its own crossings. It has been through many hands and cycles of digital and non-digital reproduction and re-use.

The level of knowledge suggests that refugees, as well as handlers and smugglers, might have been involved in the co-production of the map. The creators were aware of where to cross borders and which borders were closed, making journeys extremely dangerous because rendered illegal. The map directs people to those specific cities and places where they can access the services of smugglers or hire drivers. The map’s own social media journey directed many researchers, refugee support groups, policy-makers and media organisation to us Open University researchers, including Megan Barford at Royal Museums Greenwich.

Research Partnership with Royal Museums Greenwich

After reading our Open University Mapping Refugee Media Journeys report, Megan Barford, Curator of Cartography at Royal Museums Greenwich, got in touch with me about a new project that she was leading at the museum on migration. She was particularly interested in the map. After some discussion, we decided to do some further digging to see if we could locate the origin of this map. To our surprise, we found several versions, including ones that were hand drawn. We decided to try to uncover as many versions of the map as possible.

The Museum has now agreed to acquire the map for the museum’s permanent collection as part of a project on cartography and contemporary forced migration. As Megan says: “The acquisition of the Road to Germany map expresses a commitment on behalf of the museum to look after the map for the future, as well as for the purposes of engaging audiences and publics today. The underlying idea is to explore ways of thinking about and collecting maps where and when possible, and to capture the different ways in which maps are part of, and tell stories about, refugees’ experiences and journeys”. Even if The Road to Germany map was a vital digital map prior to the closure of the Balkan route, it is still like most digital objects an ephemeral. Once it loses use value, it will disappear out of sight and out of social media circulation, so it is important to preserve it.

The Museum and the OU are now planning further research, the aim of which is capture the material and symbolic value of this and other maps used by refugees and to document their significance. We hope to run workshops and gather more childrens’ maps of their sea crossings and to understand better the relationship of refugees to the sea. If one reflects on recent depictions of the sea then one could conclude that, especially over the last three to four years, one of the main ways in which the sea has featured in the public imagination, and in media and political discourse is through representations of the ‘migration crisis’. Mediterranean and Aegean crossings coupled with the ubiquitous re-mediation of selfies of safe passage and arrival have pervaded media coverage – often giving the impression that these crossings are easy and risk free – exacerbating fears of ‘invasion’. However, it is clear that the haunting and tragic image of Alun Kurdi’s dead body lying on the shore did not provoke the kind of EU policy response that would effectively tackle the policy crisis, the criminalisation of refugees and the enduring dangers they face – not least the rising numbers of refugees dying at sea. In 2017, the numbers of refugees dying at sea have actually risen despite the EU-Turkey deal. Bringing the consequences of forced migration and the dangers of the sea to public consciousness is important.

According to Megan: “Having material in the museum like the ‘Road to Germany’ allows our audiences to connect with the stories and crossings of refugees, and is a vital part of what maritime heritage in the 21st century should mean. The map can also encourage us to think about the UK’s response: why Britain is not on the map; why the Calais Jungle became the ‘waiting room’ for so many to cross the Channel to Britain; what will happen after Brexit to our relationship to the Channel”. Megan and I are both also interested in the implications of Brexit for the future of the how we see the sea between “us” in the UK and Europe, and where the border will be drawn if France decide that migration across the channel is a UK problem. These are risky questions but crucially important ones.

The map is a fascinating object in its own right, as well as a starting point and trigger for further research, curation and exhibition. The Museum is seeking to collect a range of maps which will enable us to explore experiences and understandings of the sea in forced migration contexts – for example, NGO’s emergency relief maps; maps showing the opening and closing of borders and the creation of fences and structures to keep refugees out; works of contemporary art which take cartographic form. Maps can be forms of storytelling as well as tools for planning and navigation as my work with children’s maps in refugee camp on the island of Lesvos revealed. Their fluid status, the movement between different formats and functions, helps us use maps to explore the relationship between culture, space and creativity. Cartography, as The Road to Germany shows, is a graphic art which, in all its forms and functions, raises questions about relationships with space and place. But maps, of course, are always partial. We hope to find out more about how that partiality plays out in the context of refugee journeys in the 21st century.

Megan was awarded £50,000 (£45,000 for acquisitions; £5,000 for project R & D) to build a collection of contemporary cartographic material concerned with forced migration from the Art Fund.

Contact our news team

For all out of hours enquiries, please telephone +44 (0)7901 515891

Contact detailsNews & articles

The FUNdamentals: Why fun matters more than we think

In a world that feels increasingly serious and pressured, fun can seem like a guilty pleasure — something optional, even frivolous. But what if fun isn’t an add on at all? What if it’s essential?