Day 109, Year of #Mygration: Memories of Migration

This week focuses on Who Are We?, an art exhibition held at the Tate Exchange last month. Dimos Sarantidis, a PhD candidate at the Open University whose own research has focused largely on refugee interventions in Greece, wrote this blog about his experience of visiting.

My own experience with migration in the past has been as a human rights lawyer and activist in Greece. So, visiting an art exhibition on migration was very interesting to me, particularly as it approached migration from different angles. There were plenty of workshops, installations, talks, and interventions simultaneously taking place in a big room on the fifth floor of the Tate Exchange. As I walked around, I found the work evoking memories and images from my work and political involvement with refugees in Greece so, here, I consider three of the most powerful and what they meant to me.

I started talking with Natasha Davis, a performance and visual artist who creates poetic and challenging interdisciplinary materials exploring body, memory, identity and migration. Together with Siobhan Campbell (OU), they have a collaborative participatory installation, focusing on floor plans of homes relating to personal migratory histories, the architecture of memory and the body as a site of memory. As we chatted about how stories of the past are interlinked with stories of the present, different lived experiences of my own started coming to me, some becoming intense as I will describe below.

While taking pictures of Natasha and Siobhan’s installation something unexpected happened. A woman dressed in white clothes, her eyes covered with a scarf, approached me. The woman was accompanied by a man wearing a doctor’s white coat and a woman dressed as a nurse. The blindfolded woman stood in fr ont of me and, in a way that reminded of an interrogation process, she loudly and sternly started asking questions: Name? Surname? Father’s and mother’s name? Nationality? Religion? Race? Colour of hair? Eyes? Papers! Where are your papers? Finally, she started singing loudly in an opera style: Papers! Where are your papers? Show me your papers! In this peculiar scene I felt somehow awkward, stirring memories of the multiple asylum seekers’ interviews I have attended as a lawyer, when similar questions were addressed to them. I remembered Farhad (pseudonym) an asylum seeker and friend, whose application had been pending for eight years. He was very experienced with asylum seekers’ interviews, since he had attended plenty of them as an interpreter. Even he, who was so well prepared for this interview and so familiar with the whole process, when his own interview started all the questions made Farhad freeze. He couldn’t speak at all. I had to ask the asylum committee to interrupt the procedure to give him a break. Farhad told me that those questions reminded him of the first time he arrived in Greece, as an unaccompanied minor. The police had arrested him and were asking similar questions. “Despite the fact that I have been living and working for so many years here (in Greece) the feeling is now exactly the same as that first day I arrived”, he told me. This scene with the blindfolded woman brought back how cruel and humiliating an asylum interview can be, or any kind of an ‘interrogation’ process. One can hardly get familiarised with such processes, even if this “interrogation” takes place as part of an artistic intervention.

ont of me and, in a way that reminded of an interrogation process, she loudly and sternly started asking questions: Name? Surname? Father’s and mother’s name? Nationality? Religion? Race? Colour of hair? Eyes? Papers! Where are your papers? Finally, she started singing loudly in an opera style: Papers! Where are your papers? Show me your papers! In this peculiar scene I felt somehow awkward, stirring memories of the multiple asylum seekers’ interviews I have attended as a lawyer, when similar questions were addressed to them. I remembered Farhad (pseudonym) an asylum seeker and friend, whose application had been pending for eight years. He was very experienced with asylum seekers’ interviews, since he had attended plenty of them as an interpreter. Even he, who was so well prepared for this interview and so familiar with the whole process, when his own interview started all the questions made Farhad freeze. He couldn’t speak at all. I had to ask the asylum committee to interrupt the procedure to give him a break. Farhad told me that those questions reminded him of the first time he arrived in Greece, as an unaccompanied minor. The police had arrested him and were asking similar questions. “Despite the fact that I have been living and working for so many years here (in Greece) the feeling is now exactly the same as that first day I arrived”, he told me. This scene with the blindfolded woman brought back how cruel and humiliating an asylum interview can be, or any kind of an ‘interrogation’ process. One can hardly get familiarised with such processes, even if this “interrogation” takes place as part of an artistic intervention.

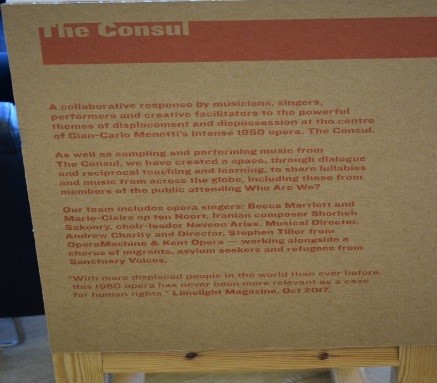

This artistic intervention was part of the ‘Tate Exchange’ event, as a ‘collaborative response by musicians, singers, performers and creative facilitators to the powerful themes of displacement and dispossession at the centre of Gian-Carlo Menotti’s intense 1950 opera, The Consul.’

This artistic intervention was part of the ‘Tate Exchange’ event, as a ‘collaborative response by musicians, singers, performers and creative facilitators to the powerful themes of displacement and dispossession at the centre of Gian-Carlo Menotti’s intense 1950 opera, The Consul.’

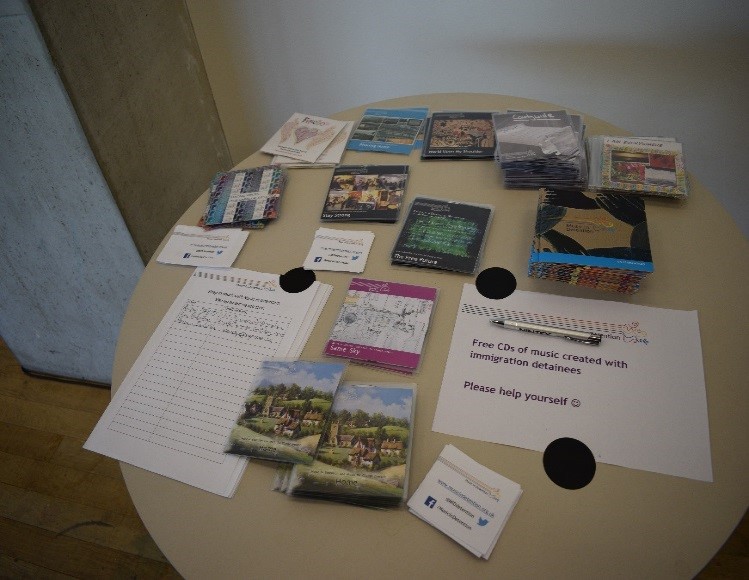

Another memory re-awoke when I saw CDs of music co-created with immigration detainees. Music in Detention works with immigration detainees, bringing them together with professional musicians and local communities to share, create and enjoy music, enabling often-ignored voices to be heard in new ways. The first image took me back to my time in Pagani (2008-2009), one of the worst border crossing detention centers in Europe. Despite its ugliness and its terrible living conditions, detainees were frequently using buckets as drums to keep the tempo and were, together, singing traditional songs from their countries of origin. However, they were not encouraged to sing. Some of the police officers complained, openly shouting for detainees to ‘shut up’ and swearing in Greek. Although border crossers could not understand any of these words, the police officers’ body language and posturing menacingly with truncheons was enough to make them stop singing. While I watched these scenes, the shouting and swearing, I was thinking that they were literally hating those detained border crossers, wanting them to be as miserable as possible. So, allowing them to sing would not serve their purposes, because singing frequently takes misery away from people.

Despite the memories the installations aroused being from my past, some 10 years old, they are relevant to contemporary issues, because of the escalating influx of border crossers into Greece who are being detained, interrogated and harassed by those who have power to do so. I found Natasha Davis and Siobhan Cambell’s installation evocative, challenging visitors to put themselves in the place of people who are in a state of forced displacement and migration. Through their installation they made me think that the condition of migration and displacement could happen to anybody, at any place and time and as an experience that is very traumatic

Despite the memories the installations aroused being from my past, some 10 years old, they are relevant to contemporary issues, because of the escalating influx of border crossers into Greece who are being detained, interrogated and harassed by those who have power to do so. I found Natasha Davis and Siobhan Cambell’s installation evocative, challenging visitors to put themselves in the place of people who are in a state of forced displacement and migration. Through their installation they made me think that the condition of migration and displacement could happen to anybody, at any place and time and as an experience that is very traumatic

Contact our news team

For all out of hours enquiries, please telephone +44 (0)7901 515891

Contact detailsNews & articles

OU gets £787k funding to reveal the hidden mineral record of Jupiter’s icy moons

An Open University team, led by Dr Mark Fox-Powell, has received a research grant with a value of £787,300 from the Science and Technology Facilities Council to transform our understanding of how surface materials on Jupiter’s icy moons record their complex histories.