Marie Skłodowska Curie still a good role model for female scientists at 150?

Sometimes I’m glad I’m old(ish) and have made it up the career ladder. I can’t imagine what it must be like to be a young woman trying to become established today. Not only are they likely to be saddled with a large debt from university tuition, they must also contend with discrimination and harassment, no matter what field they wish to enter. Academia, unfortunately, is no exception.

It is salutary to look back at the hurdles the most famous female scientist had to overcome on her journey to two Nobel prizes in separate disciplines – physics and chemistry – one of only four individuals to be honoured in this way. Marie Skłodowska Curie (November 7, 1867 – July 4, 1934) is a role model like no other – and practically the only female scientist that many people can name. She is particularly known for her groundbreaking work on radioactivity.

I reread Skłodowska Curie’s biography recently, and she certainly deserves her place of honour in any list of leading scientists. Her work impacts my own field of space sciences on a daily basis – not least as we use radioactive decay as a power source for the spacecraft that help us shed light on our solar system.

Skłodowska Curie’s life story seems more compelling than ever. She faced the problems that scientists experience today: shortage of funding, inadequate laboratory facilities and having to manage a teaching load with research time. Add to that two daughters, and the issue of juggling childcare and career adds a familiar refrain.

But she was also an immigrant. In her native country of Poland, women could not go to university, so she went to France for her higher education. She could not go until she had raised sufficient money to pay her tuition fees, so she worked as a governess for two years, finally leaving for France in 1891.

Fast forward a few years, and Maria Skłodowska, now Marie Skłodowska Curie, had overcome the difficulties of her background, and in 1903, became the joint recipient, with her husband Pierre Curie, of the Nobel Prize in physics. Surely a life of success beckoned? No such luck. Widowed less than two years later, Skłodowska Curie continued to struggle, mainly with health issues related to her research on radioactivity.

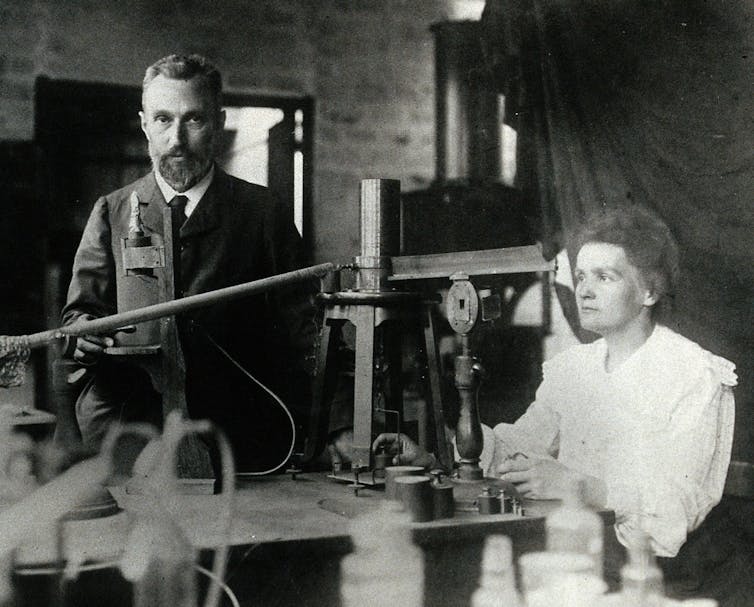

Marie and Pierre Curie. wikipedia

Marie and Pierre Curie. wikipedia

She received further honours, becoming the first female professor at the Sorbonne. But as her fame grew, again, as happens so frequently, success led to vilification. Her daughter Eve related in the 2001 autobiography: “Her origins were basely brought up against her: called in turn a Russian, a German, a Jewess and a Pole, she was ‘the foreign woman’ who had come to Paris like a usurper to conquer a high position improperly.”

Much of the vitriol came to the fore in 1910, when was nominated for membership of the Académie des sciences – an honour never previously awarded to a woman. She lost out by one vote, and the first female full member was not elected until 1979.

Modern icons?

Skłodowska Curie really is a splendid role model and a feminist icon – but you don’t have to go through all that grief, or even dissolve up several tonnes of uranium ore to serve as an example of what women can accomplish.

In my own field, there are many amazing women who have been the first in their sphere. Just think of the first women astronauts: the Russian cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, the British astronaut Helen Sharman and the US space shuttle astronaut Sally Ride.

Space shuttle astronaut, Sally Ride. wikipedia

Space shuttle astronaut, Sally Ride. wikipedia

Vera Rubin, an astronomer who discovered powerful evidence of dark matter, died recently without winning the Nobel Prize that many people thought she deserved – having suffered from sex discrimination during her entire career.

A lot of successful women in science go completely unnoticed. The recent film, Hidden Figures, highlighted the prejudices that three black women (Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson) working for NASA in the 1960s had to overcome. These women made some enormous achievements and their lack of recognition is appalling.

In the 1970s, another woman, Charlotte Whitton, the first Canadian female mayor summarised the situation women faced: “Whatever women do they must do twice as well as men to be thought half as good. Luckily, this is not difficult.” This may be a little unfair, but it did reflect the frustration of the time. Things are getting better – there are more women in positions of seniority across all fields and disciplines, and it is becoming less of a talking point when a woman is successful.

But we are still failing to develop the talents of many young women. In a society that is woefully short of the scientists and engineers that it needs, we lose a lot of the potential workforce when we fail to excite young women to continue studying science subjects like physics beyond the age of 15 in schools. And many women who do get into science fail to reach senior positions.

What role models are required to persuade girls that they can become scientists and engineers? What will persuade them that physics isn’t boring? How can we ensure that there are sufficient students in our universities to provide the specialists we will need to maintain the pace of discoveries that we have come to expect in our digital age? Is the life and example of Marie Skłodowska Curie still relevant, or do we need someone a little more contemporary?

Maybe a culture change is required – and that is more than any role model, no matter how charismatic, can enforce. As we have seen, the past is coming back to haunt men who have abused positions of privilege to harass women. Perhaps we are, at last, going to attain the equality of status that women have been fighting for for decades. Women should no longer feel under threat in the workplace. It should be a matter of no moment when a woman is appointed or promoted. The UK’s Athena SWAN charter was established to advance gender equality in STEM subjects in universities, and has been successful. There is still a long way to go, though, and ensuring equality doesn’t engender excitement.

Skłodowska Curie and her husband are immortalised as the Curie (Ci), the unit of radioactivity, and as curium (Cm), the element in the periodic table with atomic number 96. 7000 Curie is an asteroid. But it just seems such a shame that 150 years after her birth, we still haven’t got the role of women in science and engineering at the level of attainment that means we can stop talking about it.

Skłodowska Curie and her husband are immortalised as the Curie (Ci), the unit of radioactivity, and as curium (Cm), the element in the periodic table with atomic number 96. 7000 Curie is an asteroid. But it just seems such a shame that 150 years after her birth, we still haven’t got the role of women in science and engineering at the level of attainment that means we can stop talking about it.

Monica Grady, Professor of Planetary and Space Sciences, The Open University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Contact our news team

For all out of hours enquiries, please telephone +44 (0)7901 515891

Contact detailsNews & articles

Open Research Week to spotlight innovation in 2026

Open Research Week will return from 16–20 March 2026, uniting Open University researchers and partners to explore how open practices drive engagement, innovation and societal benefit.