How 17th century’s Britain’s ‘cancel culture’ can help us understand the importance of free speech

Free speech is the right to express one’s opinions without censorship or restraint. It is a cornerstone of modern liberal democracies. Nowadays, it is considered a basic right in the UN’s 1948 Declaration of Human Rights and it is is enshrined in British law.

Yet, free speech is neither historically well established nor widespread.

In many parts of the world, authoritarian governments have prevented citizens’ rights to free speech through censorship, mass detentions, surveillance and harassment. At the same time, within liberal democracies there has been growing concern about the overreach of cancelling or no-platforming those with controversial views.

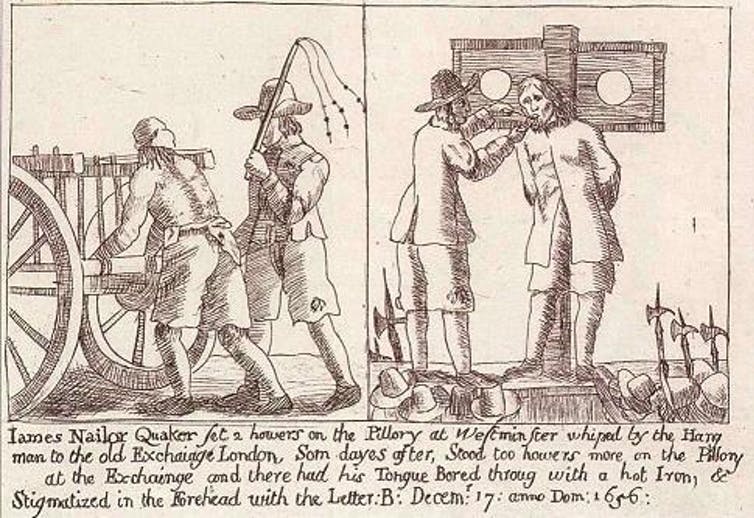

Arguments against free speech have been made for centuries. In 17th century England, saying or writing something blasphemous would have got your tongue bored through with a red-hot iron. That is what happened to the Quaker James Nayler in 1656.

Nayler engaged in a calculated provocation. He imitated Jesus Christ during a time when many of his religious contemporaries thought that the world was about to end. Other than having his tongue pierced, he was whipped through the streets of London and had his forehead branded with the letter ‘B’ for good measure.

As a punishment for blasphemy, James Nayler was whipped through the streets of London and had his forehead branded with the letter ‘B’.

Área de University of Wisconsin-Madison, History Department

Seventeenth century England was a country in crisis. For this was a time of fear, superstition, unaccountable monarchs, wars, religious strife, natural disasters, and the so-called “Little Ice Age” that severely impacted food production and transportation networks.

As well as the struggles between King Charles I and parliament, there were also rebellions in Scotland and Ireland, all of which were responsible for sparking the civil wars that took place throughout the British Isles.

There were also specific attacks on free speech. In particular, Parliament reimposed press licensing in June 1643. Essentially this system enabled specially appointed officials to suppress inflammatory texts prior to publication or else tone down controversial content.

It was amid these events that poet and polemicist John Milton wrote Areopagitica (1644). Here, he argued that press censorship was a mark of tyranny and that, despite persecution, truth would eventually prevail.

Another influential figure at the time was the Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza. For Spinoza, there were two key arguments for the right to free speech.

First, by allowing ideas and viewpoints to proliferate, societies and governments can make better decisions that are more representative of the common good. And second, speech and thought can never be truly controlled anyway. Any regime that attempts to bully and control the minds of citizens only ends up inciting resentment and rebellion.

Both Milton and Spinoza were writing in societies marked by varying degrees of censorship and surveillance. Taken together, their ideas would directly influence the Enlightenment. We may not like everything that we hear or read, they argued, but societies are stronger when the speech of one and all is protected.

Burning books

When Milton published Areopagitica, no one had been burned at the stake for heresy in England for more than 30 years. What remained, however, were public book burnings. These mass public displays can be thought of as Protestant Autos da Fé – or ritual displays of humiliation that functioned as a form of purification. They were seen by some contemporaries as echoing an aspect of the terror practised by the Inquisition that operated in several predominantly Catholic areas (a judicial institution established to eradicate heresy).

Over 100 different titles were ordered to be burned in 17th-century England, most between the years 1640–1660, when Milton was writing. While ecclesiastical and secular authorities could no longer burn the bodies of convicted blasphemers and rebels, they could still burn their books.

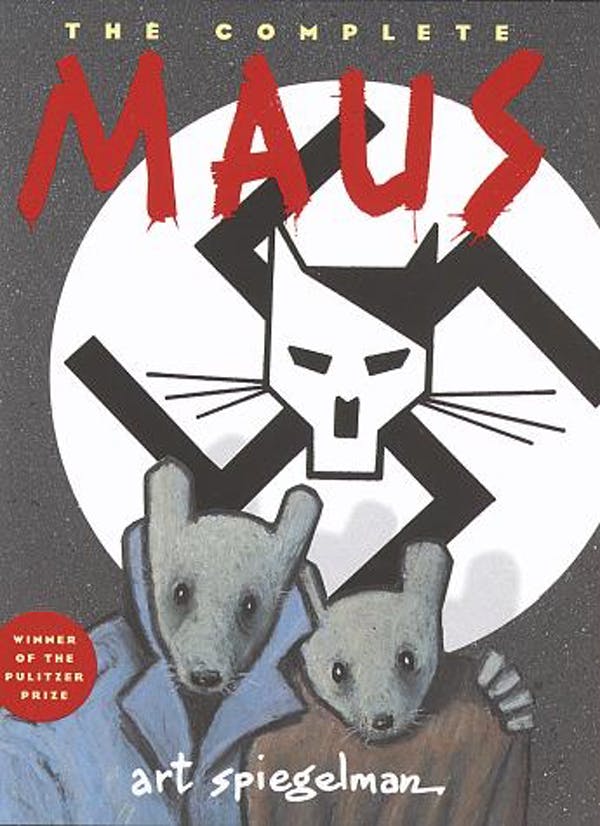

Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus details his parents’ experiences in Nazi concentration camps during the Holocaust.

lopez2k95/flickr, CC BY

Sadly, this isn’t a matter of historical curiosity. Public book burnings are still familiar even in countries supposedly committed to free speech. Just recently, in Tennessee a pastor organised a public book-burning ceremony to combat “demonic influences” and “witchcraft”.

More generally, the US has seen a growing desire to ban books deemed difficult or obscene, such as Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Art Spiegelman’s moving account of the Holocaust, Maus. The American Library Association recently reported that it’s received an “unprecedented” rise in requests to ban “objectionable” books – around 330 books in total.

That free speech is still (though only symbolically) burnt at the stake today points to the enduring challenges presented by difficult, unpopular or repugnant ideas. Suspicion against all types of censorship is a healthy sign that the public is willing and capable to make up their own minds.

Thanks to the likes of Milton and Spinoza, the attacks on free speech of the 17th century eventually gave way to a much more liberal culture in parts of western Europe. Had there not been this reaction to censorship during the early modern period, we wouldn’t have had some of the ideas of religious tolerance and democratic participation that went on to underpin the Enlightenment.

Dan Taylor, Lecturer in Social and Political Thought, The Open University and Ariel Hessayon, Reader in early modern History, Goldsmiths, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Contact our news team

For all out of hours enquiries, please telephone +44 (0)7901 515891

Contact detailsNews & articles

The FUNdamentals: Why fun matters more than we think

In a world that feels increasingly serious and pressured, fun can seem like a guilty pleasure — something optional, even frivolous. But what if fun isn’t an add on at all? What if it’s essential?